DISCLAIMER: Michael Wilson is a friend of mine IRL.

I probably do not read poetry correctly. If I’m listening to music, I generally prefer the whole album to an individual song. In fiction, I gravitate toward novels over short stories. A whole gallery is a more powerful experience than a single painting mounted on a wall. And yet, for some reason, I tend to consume poems like flash fiction or a song I might stream on Spotify or a picture I might set as my desktop wallpaper: a la carte and deprived of the textural context provided by a complete collection.

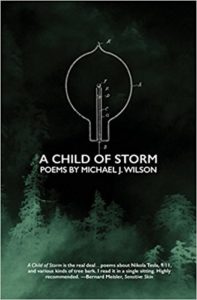

I’m glad that I made an exception this time and read Michael J. Wilson’s A Child of Storm from beginning to end because this is a group of poems that draws much of its force and weight from the strands connecting its various parts. Individually, these poems are strong, memorable, filled with vivid images, startling ideas, and unexpected rhythms, but following the progression gives the whole experience the feel of a sort of spindly dream. In fact, “dreamlike” is probably the most apt description I can think of for the experience of A Child of Storm which is evoked by its tightly designed cover: an illustration of a primitive lightbulb superimposed upon ghostly evergreens that seem to materialize from a background fog.

At its outset, A Child of Storm is quick to embrace its primary subject matter – the life and struggles of the scientist Nikola Tesla – with casual excursions into reflections on sleeping love, love lost, and the numb fury left by the vacancies of the World Trade Center not far from where Tesla set up shop in lower Manhattan, all connected by an undercurrent of frisson and electricity. While the Tesla poems borrow heavily from his biography and touch upon familiar subjects (his feud with Edison, tension with his father, financial catastrophe in New York) these are invoked more to illustrate the operations of a mind than to dwell on the events themselves. “But,” as his father says in one poem, “the church is a laboratory,” eloquently going on to praise the eyes of God (“land with no horizon”) before condemning his son to “a Babel of bullshit.”

The poems are also illustrative in the sense that they explore not Tesla’s mind so much as that of the poet and of the reader. Some clues, like the frequent returns to modern day New York and New Mexico, are obvious. Others, like the speculative autopsy of Tesla’s meditations (“Perhaps the kraken wants to end its permanent night”), are more subtle. But this oneiric floating free of tether and identity prepares us for the transition into the second half of the collection, where the scientist recedes into the background and instead we cycle through poems named after different kinds of trees, themselves also used as touchstones for half-remembered and overlapping experiences: “Close your eyes and stare into the sun / this – / the color of the great universal start button / A sky – always blue – against red O’Keefe dunes” and “You tell me to chew a birch twig and it tastes like wintergreen and / I’m shocked by the numbing : that wooden thing in my mouth –”

Toward the very end of the collection, the poems become even more unmoored from expectations of linear continuity, as several poems – “History Lessons: Santa Fe” and “Lungfish” and especially “Study (Three Seasons)” – take on the qualities of miniature epics with their own meditative and thematic sprawl. So “dreamlike” is the best descriptor for A Child of Storm because it evolves much as a vivid dream does with the utmost regard for visions and declarations but scant regard for boundaries and sequence. This is all exquisitely structured and sharply rendered. So much so that I won’t comment upon (and spoil!) the ending which, not resolving a plot as such, couldn’t be described as “a shocker,” but nevertheless drops with the brutal finality of waking up.