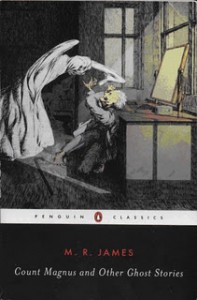

Penguin’s annotated edition of Count Magnus and Other Ghost Stories, representing approximately half the entries of the more comprehensive Collected Ghost Stories, is a fitting introduction to one of the most famous British ghost storytellers. This comes as a bit of a shock when reading the actual stories, however, for their perspective and narrative stylings are almost alien to what you’d find in more contemporary collections, whether these subscribe to the gory cult of horror or the more restrained evocation of suspense.

James’ style is a function of his background as much as of his time. Prolific during the first two decades of the 20th century, James was first and foremost a medieval scholar, and highly respected at several posts at Cambridge and Eton. James’ medieval research became the foundation for his numerous ghost stories, which he typically shared with family at annual Christmas parties, and which he was eventually persuaded to publish. While James’ scholarly work was influential at the time, his reputation today is most closely connected to these published tales of the supernatural.

Above, I described the ghost stories as feeling almost “alien,” although this is not the case in terms of subject matter. Cursed artifacts and bloodlines, ghosts and demons, Satanic ritual, and haunted sites were common tropes of ghost stories long before and after James’ writing; the actual plots of his stories are, if anything, timeless. It is their perspective, and with it a sort of unexpected rigor, that make these stories most distinctive.

For example, more than 200 years after the early Gothicists outlined a philosophical divide between terror (which withholds unpleasant information) and horror (which revels in its display), most writers of Gothic or horror literature still fall back on one of these two strategies. They share an effectiveness in our close identification with the protagonist, achieved through their emotional vulnerability, a vivid description of their experience, and presumed proximity to the reader’s own perception. James is a great fan of nested narrators, and often a story is told by a scholar who has unearthed an account of an investigator who, himself, might be hearing a supernatural tale second-hand. So we are reading an account of an account of an account. In an almost stereotypical display of British “dryness,” emotions are suppressed with expressions of politeness and propriety, and seldom break beyond generalized expressions of anxiety, fear, apprehension, or relief. In fact, in most of these stories, we only develop the most rudimentary understanding of any character, and even this is most clearly understood through our aquaintance with their their area of academic specialty. It is, therefore, difficult to empathize with characters, and thus difficult to feel a sensation of “terror” or “horror.”

This emotional detachment will be problematic for many modern horror readers, who rely almost by instinctively on an author’s ability to evoke fear, and James’ work is dated, at least in that it restricts itself to a more intellectual, more ruminatory approach to the supernatural. An underlying strategy is well illustrated in “Casting the Runes,” one of the more effective stories (and, incidentally, one of the few with sharply defined characters). In “Runes,” a medieval critic and scholar is pitted against an real-life alchemist. The annotations note that this latter figure may have been inspired by Aleister Crowley, the erstwhile Marilyn Manson of his day. Even if this were not the case, there was a deep fascination with the occult among the British upper class at this time, and “Runes” aims to appeal to this fascination far more than to evoke delicious “fear.” Thus, James reveals and withholds information about the legitimacy of Karswell’s alchemy, and hones in on the symptoms of his curse and Dunning’s strategies to escape. Personalities, motivations, and even survival are discussed in an abbreviated way and as a secondary priority.

Which isn’t to say that there aren’t creepy moments in many stories. “Runes,” itself, makes good use of suspense, as does “The Mezzotint,” “Number 13,” and “Mr. Humphrey’s and His Inheritance.” As for gristle and gore, there’s plenty to be found in “Young Hearts,” “Count Magnus,” and “Martin’s Close.” The historical detail and precision which underlies each supernatural mystery is well established, and as a result, these stories unfold as (and can be enjoyed in the same manner as) a puzzle. Even here, you might be able to guess the plot’s final destination: after all, James’ borrowed tropes that were hundreds of years old, and they have been borrowed again and again down to the present day. But the actual development of the stories are engaging nevertheless.

All things considered, the stories in Count Magnus are not particularly arresting, or mesmerizing, or affecting. They are, however, reliably intriguing… probably best read when you’re well-rested, mentally alert, and just as interested in the way a ghost story is structured as in the actual ghosts and their powers.