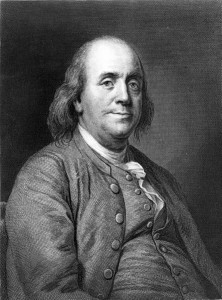

Benjamin Franklin’s 306th birthday was yesterday, January 17th.

I’m not an expert on the subject, but, as Walter Isaacson’s essay “What Would Ben Do?” notes, “[Franklin] has been vilified in romantic periods.” The question is how do we separate the spirit and content of romanticism from the momentary tropes of the/any “romantic period.” It its roots, perhaps there is something to this vilification: Franklin was a famed Enlightenment thinker, he tended toward the secular side of the religious spectrum, and he favored egalitarianism and social mobility. The romanticism of the late 1700s and early 1800s, by contrast, typically expressed a sensual engagement to faith, the elevation of emotion, and the nostalgic adoration of antiquity and nature. This oversimplifies, but these are clear points of tension.

Any -ism changes over time, and a lot of that pious yearning and neo-medieval ideations have been easily replaced by everything from Masonic symbolism to trance music. What has remained essential to romantic descendants around the world is the ascendancy of emotion; the idea that the ultimate truths — the most valid and permanent truths — are not those which can be attained by “reason” but which are derived from intuition and feeling. If you consider this superficially, as opposed to Franklin’s empirical and pragmatic approach to science, politics, even daily habits, then yes, there is indeed an opposition.

The problem with such a verdict, even from a historical point-of-view (that doesn’t consider the evolution of romantic tropes) is that it presumes the binary opposition of romanticism to empiricism, of the Romantics to the Enlightenment. Things are seldom that cut-and-dried. Many members of the Enlightenment later embraced romantic concepts, and it was a largely Enlightenment vocabulary that allowed thinkers, writers, and theorists like Immanuel Kant, Victor Hugo, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau to explore key romantic dilemmas. At its most direct and essential, the relationship could be summarized as follows: the human mind and its powers of reason are our most valuable tool to develop an understanding of the universe, but such an approach almost inevitably reveals the insufficiency of the human mind to understand everything. Self-styled “romantics” then took the further step of allowing emotion and intuition to occupy this mysterious, enigmatic place that is impervious to reason. Romanticism might be seen not as a refutation of reason, but as ancillary to it.

Which brings me back to Benjamin Franklin. Allowing that we believe in the contemporary relevance of both romanticism and of Franklin, there is just as much room for their cohabitation today as there was in the 18th century. If a utilitarian, pragmatic outlook — if useful day-to-day strategies — enables us to accomplish the most and the best of what our abilities allow, then we are not diminishing our presence in the world, but enhancing it. If such an approach is opposed to intuition, to the appreciation of the sublime, etc. etc., then yes, it is “unromantic.” But Franklin doesn’t strike one as being emotionally sterile or spiritually uninformed. He clearly embraced the validity of a wide variety of viewpoints, in philosophy, religion, and so forth… doing so is consummately “pragmatic.” If a pragmatic orientation to the world embraces romantic concepts — if it is a strategic orientation to actual problems as opposed to the dogmatic refutation of ideals — then it can be actively romantic. More, if such an orientation allows the accomplishment of great deeds — deeds which require the activation of emotional and intuitive resources — say, participation in the establishment of a new form of government — then it is actively romantic.