Unfortunately, some things are inescapable.

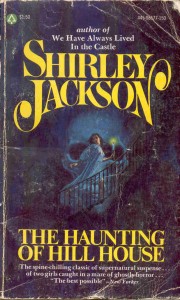

If you’ve read a “haunted house” story written in the 52 years since Shirley Jackson’s catastrophically fragile novel, The Haunting of Hill House, came out, then some of its revolutionary appeal is lost to you. I, certainly, couldn’t stop comparing it to King’s The Shining. While writers like Edgar Allan Poe had no trouble creating evil houses that destroy their inhabitants, Jackson took the additional step of routing the evil entirely through her character’s perceptions. Even if there is little doubt that we are witnessing supernatural events, we can’t understand their meaning except through the eyes of unstable and (fatally) flawed characters. This, above all, is what makes Hill House such a groundbreaking work.

Dr. Montague, a professor eager to prove the existence of “supernatural manifestations” has recruited a party to spend a summer at the reportedly-haunted Hill House. Among this group of four is Eleanor, a bitter and reclusive woman in her early thirties who has spent her young adulthood caring for her acerbic mother. The mother has died, and the story picks up steam with Eleanor’s departure for Hill House. Her journey prompts a series of enchanting fantasies, various “happily ever afters” that Eleanor imagines but cannot act upon. By the time she has arrived at Hill House, we understand her as unhappy and vulnerable, craving attention and affection but socially unable to command it, and above all filled with longing for the happiness and exuberance that has been almost entirely absent from her actual life.

Hill House itself strikes her with immediate dread, and as the other three members of the group arrive, they share in this apprehension. While the house has certainly partaken of a grisly history, its beginning is within memory, and all of the characters accept the notion that it was “bad” from the beginning; its evil was not prompted by the trace element of evil deeds from the past, but it inherent in the house itself. And for that matter, we are given some compelling explanations for this feeling. Built in a voluminous Victorian style, the house is filled with embellishments and folds, so that windowless rooms are enclosed within other rooms. The doors are constructed to close on their own, and even more striking, the floors are not level and walls do not meet at right-angles, skewing lines-of-sight and keeping the residents literally off-balance.

Some reviewers of this novel have argued that the house may not be literally haunted; that its manifestations are a product of the characters’ imaginations. I disagree. For all of the care that Jackson put into developing her characters, and the evocative and exacting description of Hill House and its environs, there is nothing that seems designed to throw skepticism on the actual occurrence of the supernatural. We are certainly meant to question the nature of the supernatural in this story, but not its actual existence. And I think this is a habit, by which literary critics try to purge quality writing of “authentic ghosts.” But however we resolve this issue, the central drama is a question of life and sanity, and given the care and precision in Jackson’s writing, the issue is immediate and plausible.

In short, maybe we can predict the plot of Hill House, and guess its literary tricks and themes well in advance, but the depth, composition, and richness of the story makes it a worthwhile read today.