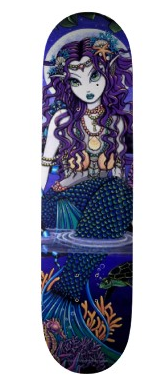

Well, the background is dark… the mermaid is presumably pallid in a slightly sickly way, given the background shining of the moon. And that turtle has a slightly malignant expression on his face. But there is little that we could call traditionally “Gothic” about this design, either in the traditional literary sense, or in terms of the contemporary Goth scene. With regards to the former, the image is drawn in anime style, with elfin features, and the atmosphere is either still or sullen; there is little motion, which is to say that there are no real heroes or villains. At the same time, if we think of traditional Goth tropes – death, decay, black-and-grays – there is little here that speaks to that aesthetic. The intense blues and greens add accents to the blacks and grays, and the image of a Lisa Frank-style mermaid is an odd choice for a movement that has always associated itself with chthonic gloom.

Nevertheless, someone has chosen to describe this mermaid image (not only for skateboards, but for postcards and posters (since I’m yoinking their images, sold here)) as “Gothic,” and has evidently had some success doing so.

I’m not arguing that it is good art… the image is lively, but the girl’s somewhat vacuous expression is a little disappointing, given the fantasy around her. Then again, there are other, unconventional reasons to call the image Gothic, and they emerge further, when we look at a more complete rendering of the original image:

Lisa Frank has entered the realm of sublimity!

The sky is studded with giant stars and planets and brilliant full moon that crowns the protagonist like a halo. The sun has recently set, and the mermaid gazes out, away from the sunset, into the night and darkness. The scene beneath and around her is awash with life and color to the point where living things alight all over her: a butterfly perches upon her “knee” and a snake entwines her arm. Below her: corals, turtles, and seahorse. She seems not to notice any of this.

The justification for this scene as a Gothic scene is perhaps best compared to the writings of Ann Radcliffe. The best examples come in the opening section of her Mysteries of Udolpho which feature page after page and description after description of majestic scenery, from the heights and horrors of the Pyrenees to the somber tones of monastery bells. There is, in fact, a long history of sublime (and sometimes overblown) physical and emotional landscapes in Gothic work, and this preference for drama – for melodrama – can be found along the length and breadth of the Gothic tradition, from the ridiculous murder that opens Walpole’s Castle of Otranto to the equally-ridiculous suicide of Ian Curtis (God rest his holy soul).

The scenes, the postcards, the skateboards depicted here are Gothic. The fact that they are successfully called such argues for the overriding thesis of this blog: that the Gothic tradition is larger and more important than it is credited for being. It has, with an uncharacteristic quietness, grown far beyond the stereotypes and tropes which have defined it for 200 years.

NOTE: I did some digging, but I couldn’t find any information on this “character” other than the products themselves. If it turns out I haven’t tunneled deeply enough after the pop-culture worm, please share any relevant details.